We see a clear pattern in our national survey of 7,028 U.S. adults, fielded August–September 2025: antisemitic beliefs are higher among Gen Z and Millennials than among older generations. For example, adults age 45 and younger are 6 percentage points more likely than older Americans to answer “mostly true” to the statement “Jewish people cause problems in the world” (9% vs. 3%).

But the takeaway isn’t simply that young people hold more antisemitic views. The findings suggest Gen Z and Millennials may be arriving at higher antisemitic beliefs through different pathways—pointing to different intervention strategies for each generation.

In the survey, we asked a battery of questions capturing multiple dimensions of attitudes toward Jewish people, including overt antisemitic beliefs, agreement with common anti-Jewish tropes, and anti-Israel sentiment. Across these measures, younger Americans (Gen Z and Millennials) show higher levels of agreement with traditional antisemitic attitudes, alongside higher levels of anti-Israel sentiment. We looked more closely at differences between the two younger generations to find the differences between the two, an interesting picture emerges:

- Gen Z shows slightly higher levels of anti-Israel sentiment than Millennials on several items.

- Millennials show slightly higher agreement with classic anti-Jewish tropes than Gen Z on multiple measures.

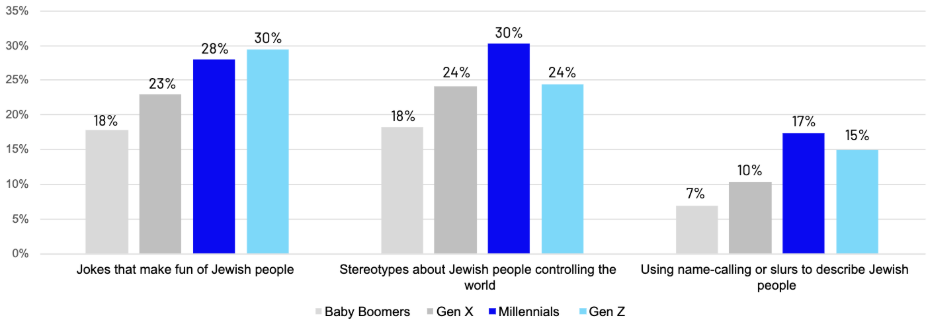

- When it comes to perceived harm, Gen Z is more likely to dismiss jokes about Jews as not harmful, while Millennials are more likely to downplay more “classical” forms of antisemitism, such as stereotypes about Jewish people controlling the world or the use of slurs/name-calling, as not very harmful to the Jewish community.

Percent of people who answered “not at all harmful” or “not very harmful” to the following

The data also points to a troubling normalization of Holocaust distortion. Younger generations are more likely to report doubts about whether the Holocaust really happened—and many say they do not consider people who question the Holocaust to be antisemitic.

The “see vs. care” gap: more exposure, less concern

One of the most striking tensions in this research is that for younger audiences, exposure to antisemitism does not necessarily translate into greater concern about it.

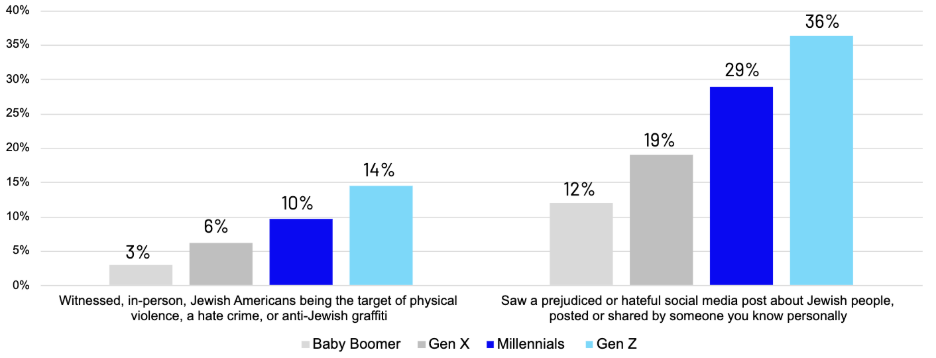

In the survey, we asked whether respondents had seen antisemitism in the past six months. Gen Z reported the highest levels of exposure both online and offline, with Millennials ranking second. For example, Gen Z was most likely to say they had seen a prejudiced or hateful social media post about Jewish people shared by someone they know personally—and they were also most likely to report witnessing in-person incidents such as anti-Jewish graffiti, hate crimes, or physical violence targeting Jewish Americans.

Percent of people who said they experienced the following in the past 6 months

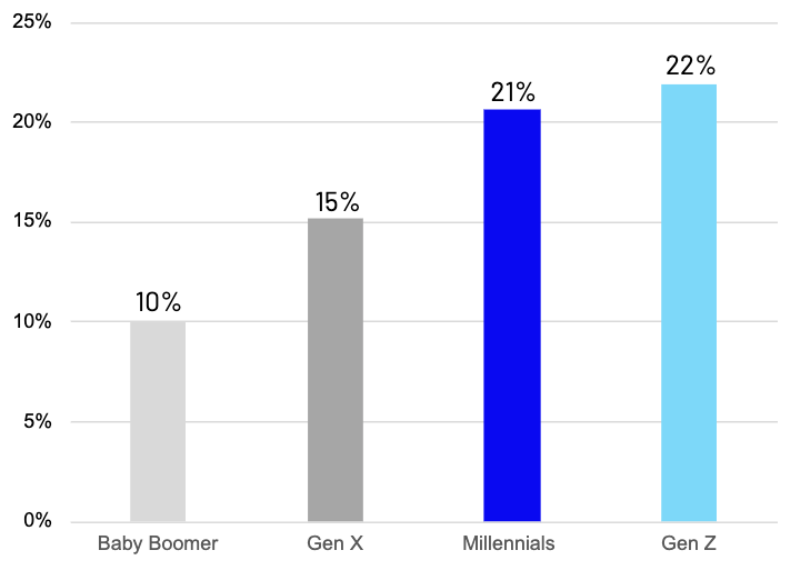

Yet despite reporting higher exposure, younger Americans are less likely to say antisemitism is a problem in the U.S. In fact, Gen Z is the most likely generation to say antisemitism is “not a problem” (22%), followed closely by Millennials (21%).

Percent of people who believe antisemitism is “not a problem”

Why this matters

Taken together, these findings point to a challenge: antisemitism is showing more often in younger people’s lives, but it’s not always being recognized for what it is—or taken seriously when it is. Sometimes it’s wrapped in politics. Sometimes it’s packaged as humor. Sometimes it’s recycled as “old stereotypes” that don’t feel urgent. And when those messages blur together day after day, they start to feel normal.

That normalization matters because it changes what people tolerate. When a slur is “just words,” it becomes easier to repeat. When Holocaust doubt is treated like an opinion, it gains legitimacy. And when antisemitism is dismissed as not a big deal, it creates room for it to grow—quietly, casually, in public, and not just online. When antisemitism becomes normalized, it becomes harder to build the social pressure that discourages it in schools, workplaces, and online communities.