The shooting at the “Chanukah by the Sea” celebration on Bondi Beach was an attack on a holiday, a community, and a feeling: that Jewish life in open public spaces can be joyful and safe. The images looked uncomfortably familiar – a public space, families out at an otherwise ordinary moment, suddenly turned into a scene of terror. And it did not happen in a vacuum. In the same week, a house decorated with Hanukkah decorations was shot at 20 times in California, two visibly Jewish people were physically attacked in New York City in separate incidents, and the FBI foiled a planned terror attack in Los Angeles ahead of New Year’s planned by a radical pro-Palestine group.

We analyzed millions of posts about antisemitism, Jewish life, and Israel after the attack to see whether there was a shift in tone and emotion on social media. What we found was not just anger or grief, but a deeper change in how people were talking about safety, visibility, and what it means to live openly as a Jew.

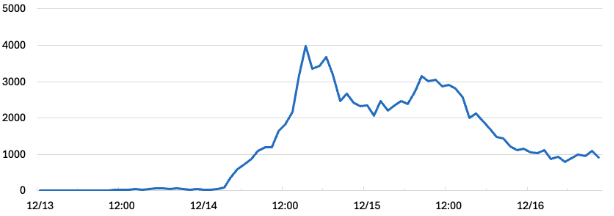

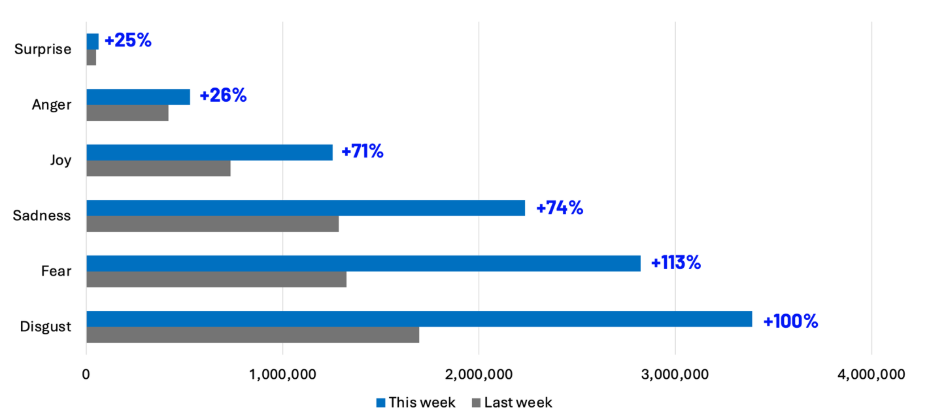

Breakdown of emotional breakdown in posts about antisemitism, Jewish life, and Israel following the Bondi Beach Shooting

Over just a few days, the emotional profile of the conversation changed sharply. Emotionally charged posts tagged as expressing fear and disgust dominated the discussion, together accounting for more than half of all emotionally coded mentions. Compared with a similar period before the attack, posts expressing fear jumped the most, by roughly 160%, while disgust rose by about 125%. Mentions of sadness also climbed steeply, but anger and surprise increased more modestly. Even posts expressing joy nearly doubled, often appearing in messages of solidarity and hopeful wishes for a happy Hanukkah.

Behind those labels are very concrete worries. The largest cluster of posts centers on fears of further terrorism and copycat attacks, with people worrying that Jewish gatherings will continue to be targeted. Another significant group focuses on Jewish spaces and everyday visibility -synagogues, schools, public Hanukkah events, and small businesses – where people ask whether it is still safe to show up as openly Jewish at all. Many also direct their fear toward institutions, accusing governments, police, and tech platforms of ignoring warning signs or failing to protect Jewish communities. Yet even within this fear-labeled sample, there is an undercurrent of solidarity and resilience, as both Jews and non-Jews describe going to public menorah lightings, organizing vigils, and insisting that Jewish life must remain visible despite the risks.

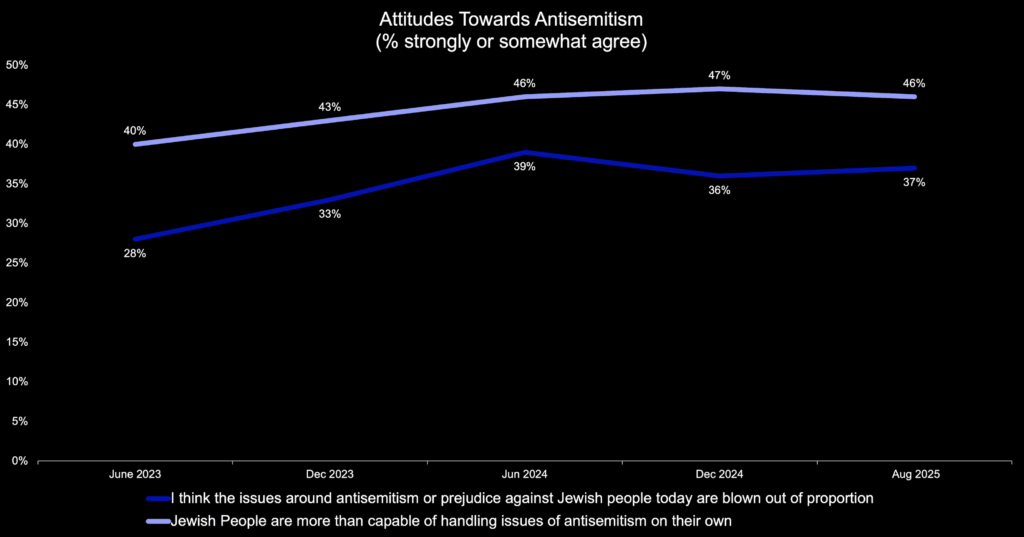

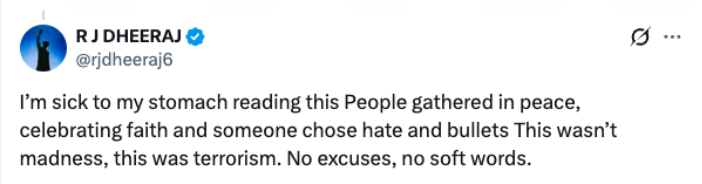

Disgust, meanwhile, is directed not only at the brutality of the attack itself, but at the atmosphere that preceded it. Many posts condemn what they see as the normalization of antisemitic rhetoric – slurs, conspiracy theories, and dehumanizing language about Jews – that has migrated from fringe forums into mainstream feeds and public protests. People criticize politicians, media, and online figures whom they see as excusing or minimizing hate, or quickly shifting the focus away from Jewish victims. In that reading, Bondi is not an inexplicable outburst, but a violent extension of what has been said out loud for months. Taken together, the data describe a world in which being visibly Jewish feels more like a calculation.

That emotional spike isn’t abstract. It is changing the most intimate parts of Jewish ritual life, including the question of whether to put a menorah in the window at all. One essay in eJewishPhilanthropy, that was published even before the Bondi Beach attack, frames this as a now-familiar dilemma: “Should I display my menorah in the window?” The author describes a fear that used to feel individual but now feels “collective… rippling through Jewish communities” as people weigh pirsumei nisa — the obligation to publicize the Hanukkah miracle — against the risk that a visible Jewish symbol could invite hostility.

The same push-and-pull is playing out in public spaces. In the days after Bondi, law-enforcement agencies in New York, Los Angeles, London, Berlin and other major cities announced increased patrols and security at synagogues and Hanukkah events, explicitly linking those measures to the Bondi Beach attack. Jewish security organizations updated threat assessments and urged communities to harden event perimeters, coordinate closely with police, and move some gatherings indoors or behind controlled entrances.

Yet the online conversation is not only about vulnerability. Alongside fear and disgust, we see messages of determination and resilience. Some posts insist on lighting Hanukkah candles in public precisely because of the attack. Others describe non-Jewish colleagues checking in, universities and local officials naming antisemitism directly, and interfaith groups organizing joint events. Resilience is also showing up through allyship: reports of non-Jewish neighbors joining Project Menorah, placing menorahs or menorah images in their own windows as a visible show of solidarity – a gesture Jews themselves debate, but one that echoes earlier moments when entire towns papered their windows with menorahs in response to antisemitic vandalism.

For many Jews watching from afar, Bondi has become another marker in a growing timeline – one more reminder that ordinary spaces can feel less certain than they once did. The numbers in our dataset are large, but the underlying story is personal: a community recalculating what it means to walk through the world as itself.