When OpenAI unveiled its new Sora app this month, it was billed as a revolutionary leap forward in artificial intelligence. Sora is a text-to-video tool that can turn written prompts into lifelike videos within seconds. The company said it would change how people tell stories, make ads, and share ideas online. But almost immediately, something else began to unfold. What was meant to empower creativity also started to fuel hate with lifelike videos that are harder to detect.

At the Blue Square Alliance Command Center, which monitors online antisemitism and extremist trends, we have been tracking how bad actors have seized on Sora to generate and spread antisemitic and other hateful content. What we’ve found reveals both the promise and the peril of this kind of technology.

An AI Tool That Makes Lifelike Videos from Simple Prompts

With Sora, a user can type a short phrase like “a man walking through New York City in the rain,” and within seconds, the app generates a realistic life-like video that appears authentic.

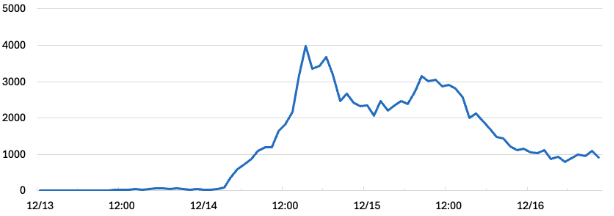

Within three days, the invite-only Sora app became the most-downloaded app on Apple’s App Store, surpassing even OpenAI’s own ChatGPT. Since launch, invite codes were shared widely across social media, dramatically expanding access to more people.

Antisemitic Tropes Surface in Sora-Generated AI Videos

Within days of Sora’s release, antisemitic AI videos began to appear both on the app and across mainstream social media platforms. Many of these clips recycled old antisemitic tropes and gave them a new digital sheen.

Some depicted stereotypical images of Jewish people surrounded by money or symbols of global power, echoing long-standing conspiracy theories. Others reimagined Nazi propaganda or portrayed Adolf Hitler in glorified or comedic ways, using Sora’s realism to make dangerous ideas seem more palatable.

While OpenAI has put guardrails in place to block violent or hateful prompts, those barriers have proven far from foolproof. Users have learned to use coded language or indirect descriptions to trick Sora into producing antisemitic or extremist videos that would otherwise be flagged.

Many of the videos spreading antisemitic rhetoric lean into the trope that Jews are inherently greedy. In one well documented video, a man wearing a kippah is seen sinking into a room of gold coins, with the comment section of the video was flooded with antisemitic language.

In other cases, AI videos were used as propaganda, depicting fake scenes from the war zone in Gaza. In one video promoting Holocaust denial, Sora created a video of famous animated character Mr. Krabs asking SpongeBob to make “6 million Krabby Patties” as a reference to the six million Jews killed in the Holocaust.

Sora’s misuse has gone beyond antisemitism. The tool is also being used to create hateful or misleading videos aimed at other marginalized groups. Some users have generated graphic videos depicting violence, racism, or xenophobia.

Others have produced misogynistic or homophobic clips, or targeted immigrants and Muslims with demeaning portrayals. The tool has also been used to create deep-fake videos of well-known individuals such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Stephen Hawking, raising serious ethical and copyright concerns.

These videos quickly migrate to mainstream social media platforms such as X, Instagram, and TikTok, where they reach far larger audiences and are shared thousands of times. Anyone scrolling through their feeds today has a high chance of encountering a Sora-generated video sometimes without realizing it.

Sora Drives Synthetic Media Growth Online

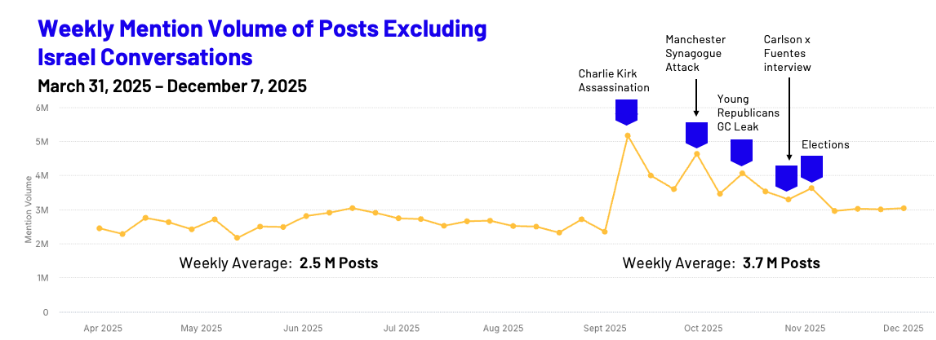

While it’s difficult to measure precisely how much Sora-generated content lives on social media, our analysis of online conversations since the app’s release shows a 216% increase in posts discussing AI-generated videos. Mentions of “Sora,” “AI video,” and related phrases have surged across major platforms, signaling both public fascination and the growing spread of synthetic media.

Sora’s Hyper-Realistic AI Videos Blur the Line Between Fact and Fiction

What sets Sora apart from earlier video-generation tools is its uncanny realism. Faces are expressive, camera movements feel natural, and lighting and shadows behave much closer to how they would in a real recording, making it much harder for viewers to tell what is real and what is fake.

OpenAI adds a watermark to all Sora-generated videos to signal they were AI-made, but users quickly found ways to remove or obscure it using guides and tools easily found online, making it much harder to distinguish Sora creations from real footage.

That realism makes the technology powerful for creativity, but also potentially dangerous. When hateful or misleading content looks real, it becomes much harder to question or debunk. A fake video of a politician, religious figure, or protest scene can spread online faster than any correction or fact-check, especially once it’s been edited and re-uploaded without context.

The Viral Reach of AI-Generated Hate: Why Sora’s Scale Makes It Dangerous

The danger isn’t just in the content itself—it’s in the reach. In today’s online environment, a convincing fake video can travel faster than any truth, as depicted by a viral video of an elderly woman feeding a bear which amassed over 44 million views. When antisemitic or extremist ideas are dressed up as slick, realistic visuals, they become easier to consume and harder to distinguish as fake.

From past research on the use of generative AI on mainstream platforms, we know that these systems have enormous potential reach. An analysis we conducted earlier this year found that within the first three months of Grok being implemented as a chatbot on X, it amassed more than 45 trillion impressions.

That scale becomes dangerous when similar AI tools are being used to spread hateful narratives. As seen with Grok—when it adopted the persona “MechaHitler” and produced openly antisemitic responses—millions of users amplified that content rather than rejecting it.

The Secure Community Network, a national Jewish security organization, recently reported that extremist groups are increasingly using AI tools to produce antisemitic propaganda, recruitment material, and operational content targeting Jewish communities across the United States. This is a pattern we’ve seen before and one that will only accelerate as AI becomes more powerful and accessible.

OpenAI’s Response

To its credit, OpenAI has taken steps to limit misuse. The company says it screens prompts for hate speech, automatically reviews flagged videos, and adds both visible and invisible watermarks to all Sora creations, although they can be easily removed. After early controversies—including inappropriate depictions of historical figures—OpenAI also began restricting the use of real people’s likenesses.

Still, our findings show that these safeguards aren’t foolproof. Just as with earlier AI systems, users find ways around filters, and once content leaves Sora’s platform, the company loses control. OpenAI has publicly acknowledged these challenges and said it is continuing to strengthen moderation and collaborate with outside experts.

A Turning Point in How Antisemitism Spreads Through Generative AI

Sora represents a new stage in the evolution of generative AI, as well as a turning point in how antisemitism spreads online. Instead of text posts or crude memes, we’re seeing high-definition, emotionally charged videos that look real enough to fool almost anyone.

These videos don’t just target Jews. They aim to normalize antisemitism by making age-old lies palatable as “jokes” and “memes.” Technology will keep advancing, and so will those who seek to misuse it. As improvements are made people will scroll through their feeds, the line between imagination and information gets blurrier, and that’s exactly what propagandists want. The challenge now is ensuring that the systems shaping our digital world don’t become vehicles for hate.

To learn how to spot AI generated content, please follow these tips & tricks.