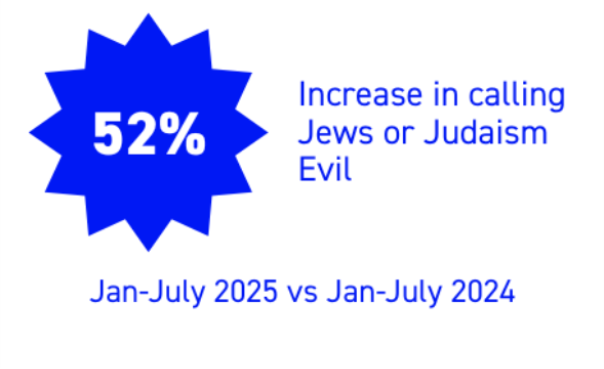

Since the start of the year, the BSA Command Center has been closely monitoring a troubling trend: hate not only spreading across the internet but becoming more profitable. Individuals and extremist groups are increasingly turning antisemitism into a business model, using tools like cryptocurrency, crowdfunding platforms, livestreaming, and merchandise sales to raise money and build influence.

While extremists have long used online spaces to organize and fundraise, what’s changed is the visibility and scale. These operations are no longer confined to fringe corners of the internet. Now, the pipeline of monetized hate runs directly through mainstream platforms — reaching wider audiences and creating financial incentives for others to join in.

Cryptocurrency: Hate in the Blockchain

One of the more insidious developments is the rise of cryptocurrencies explicitly tied to antisemitic and extremist ideologies. Cryptocurrency is a digital currency designed to work through a computer network that is not reliant on any central authority, such as a government or bank, to uphold or maintain it. These tokens often look innocuous or include coded symbols, but in reality, they operate as financial vehicles that spread hate.

These coins fall into three main categories:

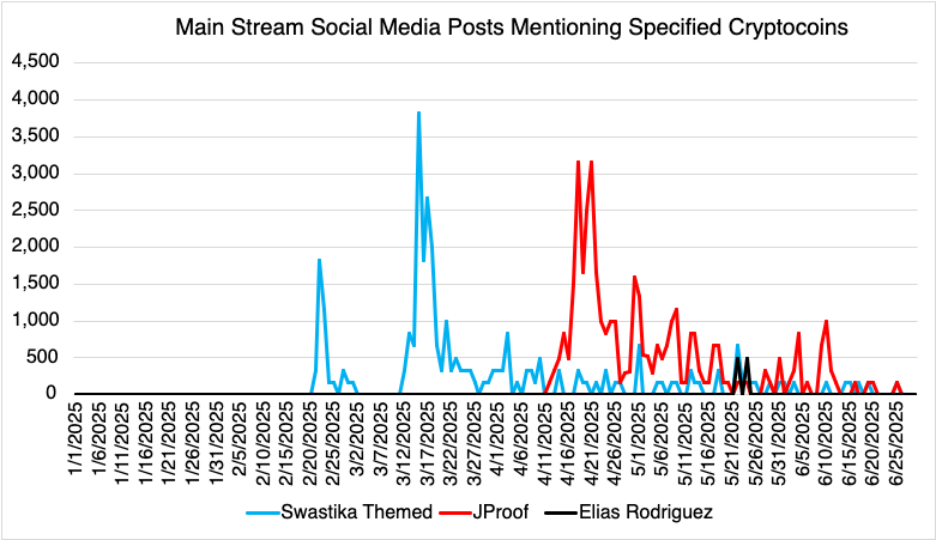

- Memecoins branded with hate: Tokens like SwastiCoin, HoloCoin, and $GROYper borrow directly from neo-Nazi and white supremacy iconography and language. Some are traded on decentralized exchanges, while others exist more symbolically — shared among extremist groups as a badge of allegiance.

- Fundraising coins for hate groups: Coins such as $JPROOF and $Proud have been launched by extremists to raise funds while evading traditional payment processors. Some of these coins appear alongside coordinated campaigns on social media, signaling their use is deliberate and strategic.

- Coins celebrating violence: Perhaps the most disturbing are coins like $Elias, reportedly created after the murder of two Israeli embassy employees in Washington, D.C., or another coin tied to the killing of Minnesota lawmakers. These coins are used to glorify acts of violence and turn perpetrators into martyrs — all while speculators stand to profit.

According to data from HolderScan — a platform that tracks real-time and historical data on crypto token holders — thousands of people currently hold antisemitic or hate-linked cryptocurrencies. We examined three tokens that represent each of the major categories outlined above. Variations of SwastiCoin, a wordplay on the swastika, is held by over 10,000 wallets. JPROOF, a coin associated with neo-Nazi figure Stew Peters, has over 3,000 wallets. And within just 24 hours of its creation, more than 550 wallets had acquired the coin celebrating the suspect accused of murdering two Israeli embassy employees in Washington, D.C.

Because of crypto’s unregulated and anonymous nature, these tokens can circulate freely — often promoted through niche forums, Telegram groups, and X accounts — with little accountability or oversight. The coins are then circulated and promoted on social media, increasing their virality and their monetary value. The graph below shows the mention volume of the three cryptocoins that are described above.

Crowdfunding Campaigns for Hate

Crowdfunding platforms have quietly become a revenue stream for individuals exposed for racist or antisemitic behavior. While some campaigns come from well-known hate actors, a growing number are launched by everyday individuals who go viral for hateful incidents and then pivot to raising money from supporters.

The platform GiveSendGo has emerged as the go-to destination for such fundraisers due to its lack of moderation and positioning as a “Christian alternative” to mainstream sites.

- Mo Khan, former Temple University student turned antisemitic influencer, raised more than $20,000 across multiple campaigns after posting videos celebrating a “f*** the Jews” sign in a Philadelphia bar.

- Shiloh Hendrix, who was caught on video yelling a slur at a 5-year-old Black child, raised over $700,000.

- “Connor”, a self-proclaimed fascist, gained notoriety after praising a Nazi writer on a viral Jubilee YouTube video. After claiming he was fired from his job, he launched a fundraiser that quickly exceeded $38,000. Many of the donations included coded white supremacist symbols — including amounts of $88 (“Heil Hitler”).

These campaigns often rely on a victimhood narrative — framing perpetrators as martyrs of “cancel culture.” In doing so, they not only raise money but publicly reaffirm hateful ideologies, giving donors a way to participate.

Livestreaming: The Hate-for-Hire Economy

Livestreaming has become one of the main — and dangerous — ways for extremists to market and monetize their hate. Extremist influencers have cultivated loyal audiences by delivering a steady stream of racist and antisemitic content, peppered with calls for donations and links to online stores.

Figures such as Nick Fuentes, Stew Peters, Jon Minadeo, and Ethan Ralph have built digital empires on this model. When banned from mainstream platforms, many have simply migrated to alternative streaming services — or launched their own. Their content blends shock value, conspiracy theories, and coded language — designed not only to retain their audience but to provoke outrage that drives engagement on social media.

Although it’s hard to estimate how much money these actors are generating this way, one estimate, published by Impact Wealth, places Nick Fuentes’s net worth between $1 million and $2 million. One step deeper, the estimated annual earnings for Fuentes just through livestreams are between $200,000 to $500,000. The outlet, however, does not disclose its sourcing or methodology, and the figures are unverified estimates.

Analysis of social media conversations shows that the notoriety of hateful figures such as Stew Peters and Nick Fuentes has dramatically increased in the past three years, especially since the end of 2022. Since 2023, the number of posts mentioning, speaking on the streams of, or interacting with Nick Fuentes and Stew Peters on mainstream social media platforms have increased by 483% and 1,362% respectively.

On many platforms, high engagement — including views, reposts, and replies — can lead to direct payouts through creator incentive programs or ad revenue sharing. For hateful actors, this means that the more attention they attract, even through inflammatory or extremist content, the more money they can make. In many cases, the antisemitic or racist ideas they promote are deeply rooted in their ideology — but the monetization model rewards that expression with visibility and income. This creates a system where spreading hate isn’t just ideological — it’s also profitable.

Merchandising Hate

The final layer of the hate economy is its merchandising arm — turning ideology into apparel. From T-shirts and hats to bumper stickers and flags, hate groups and influencers are selling branded products that double as propaganda tools.

Groups like the Goyim Defense League have built entire storefronts around this model, offering shirts that feature Holocaust denial slogans, antisemitic caricatures, or white supremacist codes. Influencers like Lucas Gage and Stew Peters do the same, selling items that both fund their platforms and help spread their messaging in public spaces.

These products serve multiple purposes: they signal allegiance, provoke confrontation, and bring hate into the physical world — all while generating steady streams of revenue. For example, the Goyim Defense League sells shirts featuring Nazi imagery and reading “Auschwitz Oven Dodgers” for $20 to $50, and “swastika soaps” reading “wash the Jews away” for $10 each.

Staying with Nick Fuentes as a case study, Impact Wealth estimates that Fuentes nets between $50,000 to $150,000 annually from selling hateful merchandise.

Conclusion: Monetizing Hate in the Mainstream

The infrastructure of hate has evolved — from anonymous forums and shadowy chat groups into a highly visible, financially viable pipeline. Cryptocurrency, crowdfunding, livestreaming, and merchandise is transforming antisemitism from a fringe belief into a monetized online ecosystem.

What makes this especially dangerous is the normalization of these tactics. The more people see others profiting from hate — and getting rewarded for it — the more the barrier to entry erodes. Bigotry becomes a business opportunity.

In this new reality, the challenge isn’t just identifying hate speech — it’s recognizing and dismantling the machinery that turns it into cash.